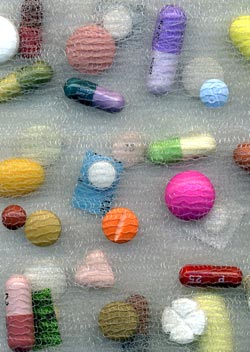

The Pills

How we charted the pills

The first decision was which kinds of medication would be used. I initially reviewed the National Prescribing data to find out which were the most commonly prescribed medicines. National prescribing data provides figures for the number of actual prescriptions written for different classes of drugs. These are further broken down by age and sex so for example it is possible to see what percentage of antidepressant prescriptions are given for women between the ages 35-44, or for men over the age of 75. I discussed these figures with the chief pharmacist for the North Bristol Primary Care Trust. He also gave me outline figures for the amount of money spent each year on different OTC - over the counter medicines.

At the suggestion of Joe Collier, Professor of Pharmacology at St George's Medical School, I also talked to the chief pharmacist at my local district general hospital about prescribing for patients while in hospital. He provided me with figures specifically relating to hospital patients, these included a child with asthma, a woman giving birth, a man with a heart attack, a man with a fractured leg and a woman with a hip replacement.

I then returned to my own patient records to find one or more patients whose own history of illness and prescribing reflected the national prescribing picture. Unsurprisingly there was no single patient whose real history reflected that of 'everyman'. It was therefore necessary to draw on a number of different patient records in order to create our composite woman and man.

The woman was composed in the following way. I took the record of a healthy woman at the age of twenty and reviewed her prescriptions. Antibiotics and immunisations and some paracetamol in the form of syrup were documented as having been prescribed in early childhood. I estimated that considerably more paracetamol as well as ibuprofen would have been bought over the counter to treat minor illnesses. As a teenager she had consulted about painful and heavy periods and later been started on the pill. She had taken a gap year and been travelling requiring immunisations, anti malarial tablets and treatment for traveller's diarrhoea. From this information I constructed a chart of the first twenty years of her life.

This pattern was repeated using four different patient records from which I charted a complete life. The second patient record was that of a woman of forty who had two children and one miscarriage plus an episode of post natal depression in the previous twenty years. The third was a woman of sixty five who had taken HRT for the management of her menopausal symptoms. Later she had been diagnosed with breast cancer and taken the chemotheraputic drug tamoxifen for five years. The fourth and final patient was a woman in her early eighties. During the previous ten years she had developed both arthritis and diabetes. Our 'everywoman is still alive at the end of the piece.

The man was also a composite derived from the notes of four different men starting with the records of a healthy twenty year old. As with the girl, immunisations, occasional antibiotics and paracetamol had been prescribed. As a child he developed asthma for which he was prescribed inhalers. During his childhood he has two severe attacks of asthma for which he is treated with steroid tablets. As a teenager he develops hay fever and for more than a decade he takes antihistamine tablets for this every spring and early summer. He grows out of both his asthma and his hayfever as he gets older. From the second medical record we track him through the healthy years of his twenties and thirties. He travels briefly to the Far East, breaks his leg playing football, is occasionally troubled by indigestion and makes the first of several attempts to stop smoking.

His third record starts in his early forties with worsening indigestion. He takes antacids and acid suppressing medication intermittently until he is tested for the Helicobacter which is a bacteria that inhabits the stomach often leading to indigestion. Following a positive test he takes a two week course of Helicobacter eradication therapy and is cured. In his fifties an episode of back pain keeps him off work for several weeks. His fourth record sees him enter his sixties with high blood pressure. Initially this is treated with one tablet a day, but over a period of years a second and then third are added. In his seventies, having finally stopped smoking he has a heart attack. For his last year he is taking an aspirin a day and a cholesterol lowering drug as well as blood pressure medicine, interspersed with fairly regular pain killers. At seventy six, and without warning he suffers a massive stroke from which he dies.

In order to construct the story of one life from these four different medical records certain additions or omissions were made. For example the elderly diabetic woman was obese but the sixty five year old was not. Our 'everywoman' takes weight reduction tablets in her mid fifties which neither of the real patients did. I include this as a way of introducing the notion of obesity as a significant risk factor for the later development of diabetes and knee and hip arthritis. Similarly a one month course of an ulcer healing drug is taken by 'everywoman' at the age of forty although this did not occur in the real medical record. This forms a link between the younger and older woman as the latter takes ulcer healing drugs with her arthritis tablets. The young man is given hay fever treatment for the same reason although this did not occur in the real record.

Most people's prescribing history contains short prescriptions for conditions that never develop into long term problems. A good example is migraine tablets which some people take regularly for years while others take them only a few times before the migraines resolve. Some medications like these that are documented in the real medical records have been excluded.

Further simplification has been achieved by limiting our choice of antibiotic to two main types (with the exception of helicobacter eradication therapy). We know that these are the most commonly prescribed antibiotics and that 70% of antibiotic prescriptions nationally are for amoxycillin. The individual records do show a predominance of this antibiotic but nearly all contain a much wider variety of antibiotic prescribing. For every documented prescription for antibiotics such as co-amoxiclav, trimethoprim, clarythromycin, cephalexin etc.. we have substituted amoxycillin and flucloxacillin.

Our final manipulation was to chose one formulation for each tablet or capsule and use it consistently throughout the piece. For example there are numerous ways you can take paracetamol including tablets of different shape and size, capsules or syrup. Most people take it in most of these different forms during their lifetime. We have chosen one of these and used it throughout, with the exception of years 0 to 12 when a lower dose and therefore different pill was necessary.

How we chose the pills

Having decided which kinds of pills we were going to use we then had to choose exactly which formulations to use. Several considerations guided our final choice.

-

Size, shape and colour

The size, shape and colour of the pills was influenced by aesthetics and practicality. Very large and very small pills cannot be incorporated in the fabric and so were rejected. Different shapes were chosen to allow us to distinguish between some of the very commonly prescribed white tablets such as paracetamol and co-proxamol. Others were selected because of their interesting shape. An example is diclofenac which comes in many different formulations including a pale pink triangular tablet which was the one we have chosen to use. Colour has been an important factor in the choice of one drug over another. Of the ulcer healing drugs we picked lansoprazole because of its colourful purple and mauve capsule. Where two formulations were equally appropriate we tended to choose the most colourful. Many drugs are white. In order to distinguish between them and to add colour to the piece some of these are shown still in their colourful packaging.

-

Familiarity

The drug fluoxetine is an antidepressant that is made by many different manufacturers. Its most common brand is known as prozac which is a cream and green capsule. We chose this over the other brands because it is the one people will recognise. Similarly with the contraceptive pill there are many to choose from. We used two different kinds, the first microgynon because it is the most commonly prescribed contraceptive in the UK and therefore most recognisable. The second was chosen more for its blue coloured packaging. It should be mentioned that although selecting for clarity in the overall piece we inevitably reflect the commercial aesthetic of the drug packaging, making the point that the manufacturer or marketing team have already made an aesthetic decision, an aspect we are commenting on.

-

Cost

For many drugs there are different formulations that are cheaper than others. Where all other things were equal in terms of aesthetics we chose the cheaper option. Sometimes we could limit the use of very expensive drugs. For example both the man and the woman take a course of anti-malarial tablets. We opted to give the woman who took a six month course the much cheaper tetracycline, and the man who only needed a few weeks treatment the very expensive drug malarone. As with the aesthetic argument, we are making a comment on cost here, not just cutting corners in the making of the piece.

-

Durability

A large number of different formulations of all the drugs we might want to use were tested at the British Museum for their durability over time. They were put under lights and in heat for the equivalent of eight years in the gallery. Some disintegrated, many faded. This helped us make our final decision about which to use as some were ruled out completely.